By Sarah C. Phillips, Senior Manager of Policy & Advocacy, Georgia Watch –

Medical Debt in Southwest Georgia

Medical debt accounts for more than half of all personal debt, affecting the lives of insured and uninsured people alike. In Georgia, where our rate of uninsured individuals is third highest in the nation and our lawmakers have rejected Medicaid expansion, medical debt traps already cash-strapped Georgians into a cycle of poverty. Southwest Georgia has some of the highest insurance premiums in the country, primarily due to the lack of competition among providers and insurers. This level of consolidation leaves consumers with minimal choice regarding where to seek care and perpetuates unfair medical billing practices. While 19% of people in Georgia have a medical bill in collections, this amount increases to 21% among people of color (Community Catalyst, 2021). This proportion is even higher in Dougherty County, home to the city of Albany and Phoebe Putney Memorial Hospital, where 25% of people of color have a medical bill in collection (Urban Institute, 2020). Data show black and brown people are the most impacted by unaffordable healthcare and medical debt. Therefore, hospitals must develop their community benefit, billing, and collections policies through a racial justice and health equity lens.

Georgia Watch, Georgians for a Healthy Future (GHF), and SOWEGA Rising aim to protect consumers in Southwest Georgia from unaffordable medical bills and debts so that all Georgians can afford the care they need. Our organizations are:

- Asking community members, especially people of color who have been disproportionately impacted by medical debt, to share their stories of medical bills, debt, and unfair debt collection practices.

- Translating the stories and experiences of community members into policy recommendations for hospitals and state leaders that alleviate the disproportionate impact of medical debt and unfair billing practices on people of color.

- Training community members to lead effective advocacy to increase their involvement in the upcoming community health needs assessment process and align local health system community benefit spending and financial assistance with those needs.

What is a Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA)?

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires non-profit hospitals to conduct a community health needs assessment (CHNA) every three years. Through the CHNA process, information is collected from community members and secondary sources about the health status of the community. Community health needs are then prioritized based on the needs assessment findings. Hospitals must implement programs that target the prioritized community health needs. They also must make their CHNAs publicly available on their websites and report program implementation progress annually to the IRS on Form 990 for tax-exempt organizations.

Phoebe Putney’s CHNA

Phoebe Putney is the largest hospital system in southwest Georgia and serves much of Albany and the surrounding counties, including Dougherty, Terrell, Lee, Worth, and Mitchell. Phoebe’s last CHNA was completed in 2020, meaning they will complete another one this year. To better understand Phoebe’s progress in addressing the significant community health needs identified in past CHNA’s, Georgia Watch reviewed CHNAs from 2013, 2016, and 2020.

In preparation for each CHNA, Phoebe forms an Internal Assessment Team consisting of hospital staff, hospital board members, and strategic community partners located within the hospital’s aforementioned five-county service area. The Internal Assessment Team defines its “community” as these five counties for the purpose of data collection and assessment. In each CHNA, key demographics are outlined, providing an analysis of variables such as ethnicity, unemployment, poverty, education levels, and health outcomes.

Community Engagement to Identify Health Needs

During the CHNA process, Phoebe conducted community interviews to identify critical health issues within its service area. Interviews were conducted with stakeholders and leaders who work directly in health improvement areas, including public health, faith-based organizations, the United Way, and various health-related charities. However, interviews were not explicitly conducted with patients and community members who do not work in health improvement. While the key leaders may possess valuable information regarding prominent health concerns in the area, they may not have the same perspectives or experiences as a community member who does not work in a healthcare or healthcare-adjacent role.

Additionally, the hospital held large-audience input sessions so community members could provide feedback on health priorities and concerns. In these input sessions, attendees reviewed local data and formulated health priorities. This practice helps mitigate the lack of variety in interviewees. However, one-on-one interviews with patients or those from more vulnerable populations may still be valuable. These groups can share firsthand experiences and be more adequately represented when priorities are identified, thereby further engaging the community.

Prioritizing Community Health Needs

Findings from the interviews and public input sessions were coupled with quantitative data collected by the hospital on health, economic factors, education, public safety, and social interviews. An internal team at Phoebe analyzes both the qualitative and quantitative data to identify the top three or four community health priorities. The size of the population affected, the severity of the problem, the health system’s ability to impact the need, and the availability of internal and external resources are all criteria used to determine which health-related issues should be considered priorities. This may pose a discrepancy in the selection process if any criteria are conflicting. For example, if an issue is deemed a severe problem that impacts a large portion of the population, but the hospital does not presently have the resources to address it, then the issue is either considered less of a priority or not a priority at all.

In 2013, the CHNA prioritized four main issues: maternal, infant, and child health, and reproductive responsibility; mental health and substance abuse; obesity and related acute, chronic diseases; and health literacy, promotion, and awareness. In 2016, the CHNA identified three areas of concern: birth outcomes and reproductive responsibility; chronic diseases; and behavioral health and addictive diseases. Lastly, in 2020, four primary issues were targeted: birth outcomes and reproductive responsibility; diabetes management and prevention; cancer prevention and treatment; and behavioral health and addictive disease advocacy.

Once the priorities are defined, Phoebe implements strategies to address the issues in the community. For example, reproductive responsibility was a critical priority in the past three CHNAs. In, 2013 the hospital sought to continue funding Network of Trust programs that provide evidence-based sex education curricula to decrease teen pregnancy, conduct school nurse training programs, and expand a sexual abstinence program. In 2016 Phoebe Putney amended the implementation strategy to include a Phoebe school nurse program that would provide HIV/AIDS and education about sexually transmitted infections (STIs) to school-aged children, specifically in Dougherty County. In 2020, the hospital included the HIV/AIDS and STI prevention program in Dougherty County schools in its implementation strategies again.

Phoebe Putney’s Financial Assistance Policy as a Component of the CHNA

Acknowledging the disproportionately high poverty levels in the community, Phoebe introduced its Financial Assistance Policy (FAP) in the 2016 CHNA to fulfill its mission as a not-for-profit charitable corporation. The FAP states that the Phoebe Putney Hospital System (PPHS), along with the Phoebe Physician Group, will provide financial assistance to those who are uninsured or under-insured and do not qualify for government programs but are unable to pay for necessary medical care. Reduced payments or free care for non-elective services may be provided, depending on the patient’s financial need. Eligible patients include those who have limited or no health insurance, can prove financial need, are legal residents of a county within Phoebe Putney’s service area, and possess less than $175,000 in assets. PPHS states that it will attempt to work with all patients to establish an appropriate payment arrangement if the payment cannot be made entirely at the time of service.

Recommendations

The CHNAs conducted by Phoebe provide a glimpse into the health-related issues impacting the community most. While we recognize the significant efforts that the hospital has made to engage its community, we acknowledge the need for additional work so that Phoebe is equipped to respond to the most critical needs. Phoebe should intentionally gather input from members of vulnerable populations when identifying community health needs and during the prioritization and implementation processes. We also recommend that the hospital promote an ongoing feedback mechanism so that community members can easily share their evaluations of the CHNA and its program implementation. By involving the community in the selection and prioritization of these needs, the hospital can ensure that its implementation strategies genuinely reflect the needs of those they serve. By implementing these additional steps, we believe Phoebe Putney will learn from community members that medical debt and unfair billing practices profoundly impact the community. Thus, Phoebe can prioritize strategies to reduce medical debt in future CHNAs.

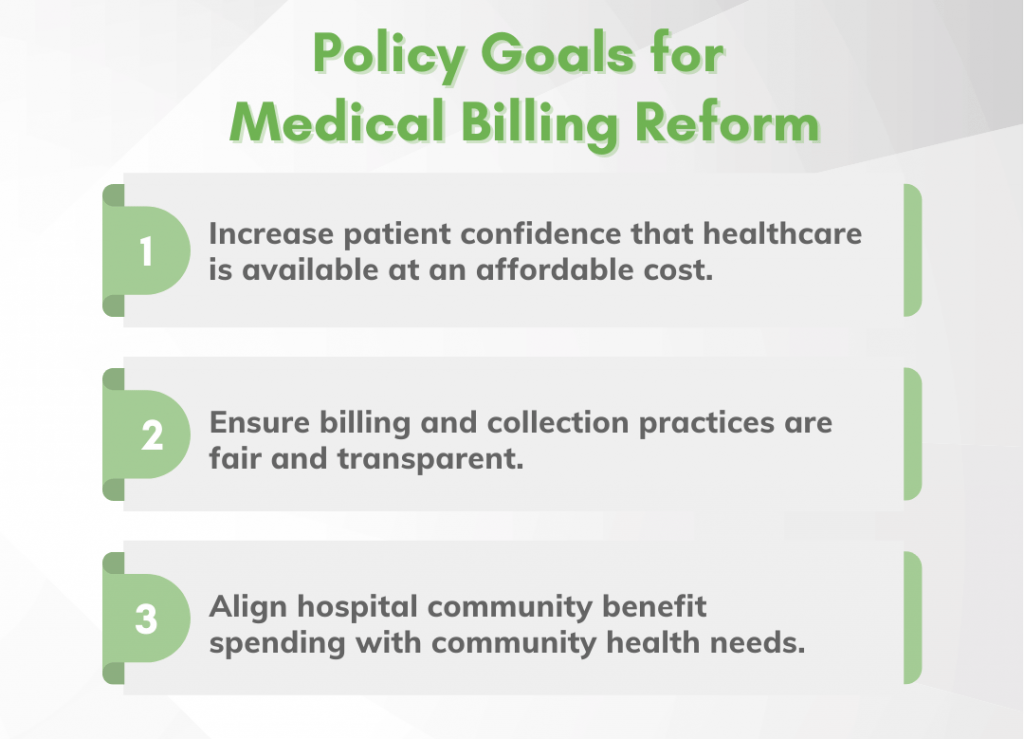

In collaboration with Phoebe Putney, our partners at GHF and SOWEGA Rising, and the community, we hope to accomplish the following goals:

Additional Resources

To read our report evaluating Georgia non-profit CHNAs and to find out more about IRS regulations for non-profit hospitals, visit the following resources: